It was the greatest infrastructure project the world had ever seen. When the 48 mile-long Panama Canal officially opened in 1914, after 10 years of construction, it fulfilled a vision that had tempted people for centuries, but had long seemed impossible.

“Never before has man dreamed of taking such liberties with nature,” wrote journalist Arthur Bullard in awe.

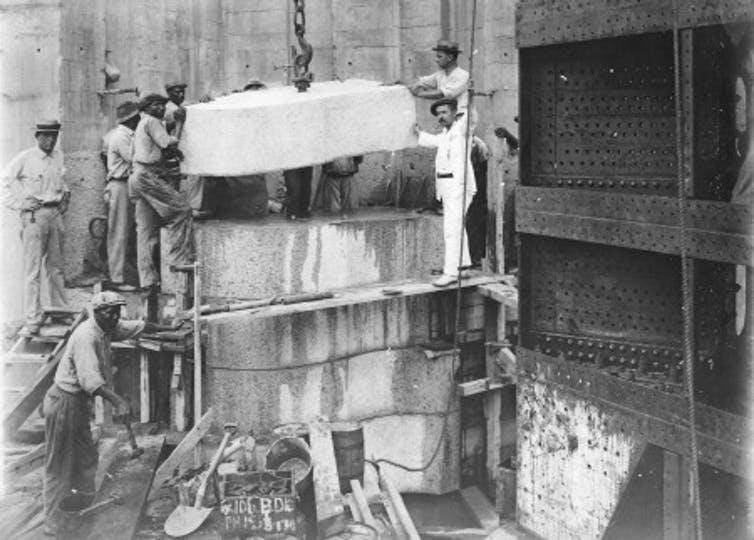

But the project, which employed more than 40,000 laborers, also took immense liberties with human life. Thousands of workers were killed. The official number is 5,609, but many historians think the real toll was several times higher. Hundreds, if not thousands, more were permanently injured.

How did the United States government, which was responsible for the project, reconcile this tremendous achievement with the staggering cost to human lives and livelihoods?

It handled it the same way governments still do today: It doled out a combination of triumphant rhetoric and just enough philanthropy to keep critics at bay.

From the outset, the Canal project was supposed to cash in on the exceptionalism of American power and ability.

The French had tried — and failed — to build a canal in the 1880s, finally giving in after years of fighting a recalcitrant landscape, ferocious disease, the deaths of some 20,000 workers and spiralling costs. But the U.S., which purchased the French company’s equipment, promised they would do it differently.

First, the U.S. government tried to broker a deal with Colombia, which controlled the land they needed for construction. When that didn’t work, the U.S. backed Panama’s separatist rebellion and quickly signed an agreement with the new country, allowing the Americans to take full control of a nearly 10-mile-wide Canal Zone.

The Isthmian Canal Commission, which managed the project, started by working aggressively to discipline the landscape and its inhabitants. They drained swamps, killed mosquitoes and initiated a whole-scale sanitation project. A new police force, schools and hospitals would also bring the region to what English geographer Vaughan Cornish celebrated as “marvellous respectability.”

But this was just the beginning. The world’s largest dam had to be built to control the temperamental Chagres river and furnish power for the Canal’s lock system. It would also create massive Gatún Lake, which would provide transit for more a third of the distance between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

The destruction was devastating. Whole villages and forests were flooded, and a railway constructed in the 1850s had to be relocated.

The greatest challenge of all was the Culebra Cut, now known as the Gaillard Cut, an artificial valley excavated through some eight miles of mountainous terrain.

More than 3.5 billion cubic feet of dirt had to be moved; the work consumed more than 17 million pounds of dynamite in three years alone.*

Imagine digging a trench more than 295 feet wide, and 10 storeys deep, over the length of something like 130 football fields. In temperatures that were often well over 86 degrees Fahrenheit, with sometimes torrential rains. And with equipment from 1910: Dynamite, picks and coal-fired steam shovels.

The celebratory rhetoric masked horrifying conditions.

The Panama Canal was built by thousands of contract workers, mostly from the Caribbean. To them, the Culebra Cut was “Hell’s Gorge.”

They lived like second-class citizens, subject to a Jim Crow-like regime, with bad food, long hours and low pay. And constant danger.

In the 1980s, filmmaker Roman Foster went looking for these workers; most of the survivors were in their 90s.

Only a few copies of Fosters’s film Diggers (1984) can be found in libraries around the world today. But it contains some of the only first-hand testimony of what it was like to dig through the spiny backbone of Panama in the name of the U.S. empire.

Constantine Parkinson was one of the workers who told his story to Foster, his voice firm but his face barely able to look at the camera.

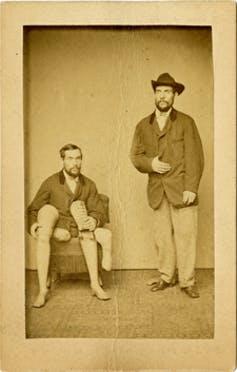

He started work on the canal at 15 years old; like many, he may have lied about his age. He was soon a brakeman, probably on a train carrying rocks to a breakwater. On July 16, 1913, a day he would never forget, he lost his right leg, and his left heel was crushed.

Parkinson explains that his grandmother went to the Canal’s chief engineer, George Goethals, to ask for some sort of assistance. As Parkinson tells it, Goethals’s response was simple: “My dear lady, Congress did not pass any law … to get compensation when [the workers] [lose limbs]. However, not to fret. Your grandson will be taken care of as soon as he [is able to work], even in a wheelchair.”

Goethals was only partly right.

At the outset, the U.S. government had essentially no legislation in place to protect the tens of thousands of foreign workers from Barbados, Jamaica, Spain and elsewhere. Administrators like Goethals were confident that the laborers’ economic desperation would prevent excessive agitation.

For the most part, their gamble worked. Though there were scandals over living conditions, injuries seem to have been accepted as a matter of course, and the administration’s charity expanded only slowly, providing the minimum necessary to get men back to work.

In 1908, after several years of construction, the Isthmian Canal Commission finally began to apply more specific compensation policies. They also contracted New York manufacturer A.A. Marks to supply artificial limbs to men injured while on duty, supposedly “irrespective of colour, nationality, or character of work engaged in."

There were, however, caveats to this administrative largesse: the laborer could not be to blame for his injury, and the interpretation of “in the performance of … duty” was usually strict, excluding the many injuries incurred on the labor trains that were essential to moving employees to and from their work sites.

Despite all of these restrictions, by 1912, A.A. Marks had supplied more than 200 artificial limbs. The company had aggressively courted the Canal Commission’s business, and they were delighted with the payoff.

A.A. Marks even took out a full-page ad for their products in The New York Sun, celebrating, in strangely cheerful tones, how their limbs helped the many men who met with “accidents, premature blasts, railroad cars.” They also placed similar advertisements in medical journals.

But this compensation was still woefully inadequate, and many men fell through its deliberately wide cracks. Their stories are hard to find, but the National Archives in College Park, Md., hold a handful.

Wilfred McDonald, who was probably from Jamaica or Barbados, told his story in a letter to the Canal administrators on May 25, 1913:

I have ben Serveing the ICC [Isthmian Canal Commission] and the PRR [Panama Railroad] in the caypasoity as Train man From the yea 1906 until my misfawchin wich is 1912. Sir without eny Fear i am Speaking Nothing But the Truth to you, I have no claim comeing to me. But for mercy Sake I am Beging you To have mercy on me By Granting me a Pair of legs for I have lost both of my Natrals. I has a Mother wich is a Whido, and too motherless childrens which During The Time when i was working I was the only help to the familys.

You can still hear McDonald’s voice through his writing. He signed his letter “Truley Sobadenated Clyante,” testifying all too accurately to his position in the face of the Canal Zone’s imposing bureaucracy and unforgiving policies.

With a drop in sugar prices, much of the Caribbean was in the middle of a deep economic depression in the early 1900s, with many workers struggling even to reach subsistence; families like McDonald’s relied on remittances. But his most profound “misfortune” may have been that his injury was deemed to be his own fault.

Legally, McDonald was entitled to nothing. The Canal Commission eventually decided that he was likely to become a public charge without some sort of help, so they provided him with the limbs he requested, but they were also clear that his case was not to set a precedent.

Other men were not so lucky. Many were deported, and some ended up working on a charity farm attached to the insane asylum. A few of the old men in Foster’s film wipe away tears, almost unable to believe that they survived at all.

Their blood and bodies paid mightily for the dream of moving profitable goods and military might through a reluctant landscape.

*Editor's Note, April 20, 2018: A previous version of this article wrongly stated that more than 3,530 cubic feet of dirt had to be moved for the Culebra Cut, when, in fact, it was more than 3.5 billion cubic feet that had to be excavated.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Caroline Lieffers, PhD Candidate, Yale University

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?