There are a lot of things to keep track of as a business owner, with payroll taxes being one of them. The IRS requires you to withhold payroll taxes on your employees’ earnings and also contribute payroll taxes. This process can be complicated if you aren’t prepared. Read on to learn the difference between income and payroll taxes, how to pay payroll taxes, how to calculate payroll, your payroll tax deposit schedule, and more.

Employment taxes include both payroll taxes and income taxes. It’s important to understand the difference between income tax and payroll tax. Payroll taxes are shared with your employee—both of you contribute the same percentage based on employee wages. Unlike income taxes, payroll taxes fund social insurance programs.

Income tax is paid strictly by the employee. This tax includes federal income tax and may also include state and local income taxes. Income tax is based on an employee’s W-4 and filing status.

There are more taxes that you’ll have to keep track of, like FUTA (Federal Unemployment Tax Act) tax. For this article, we’re going to focus only on paying payroll taxes.

Payroll taxes include the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) tax. FICA tax has two components: Social Security tax and Medicare tax. FICA tax benefits retirees, the disabled, and children.

Social Security provides benefits for retired workers and:

Medicare taxes benefit people 65 years or older, children with disabilities, and qualifying health conditions regardless of age.

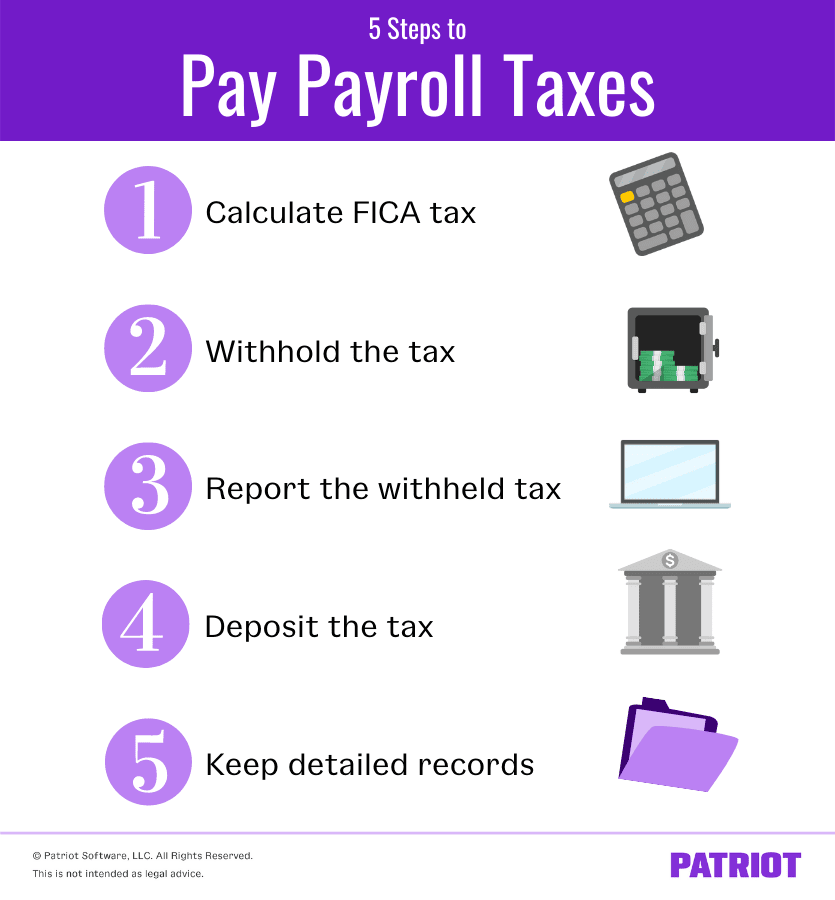

Now that you know what makes up payroll taxes, you’ll need to know the next steps to take. To pay payroll taxes, you must:

FICA tax is shared evenly between you and your employee (you both pay the same percentage of employee wages). The total FICA rate is 15.3%, which breaks down to 12.4% for Social Security and 2.9% for Medicare.

For Social Security: You and your employee each pay 6.2% (half of 12.4%).

To calculate your portion of Social Security, multiply the employee’s gross taxable wages by .062. This is also the amount you must withhold from employee wages.

Only withhold and contribute Social Security taxes on wages up to the Social Security wage base.

For Medicare: You and your employee each pay 1.45% (half of 2.9%).

To calculate your portion of Medicare, multiply your employee’s gross taxable wage by .0145. This is also the amount you must withhold from employee wages.

There is no wage base for Medicare taxes. You may also need to withhold an additional 0.9% on wages earned above the additional Medicare tax threshold.

Let’s take a look at an example.

Maria’s annual pay for 2021 is $60,000. Maria is paid biweekly. Her biweekly check, before taxes, would total approximately $2,307.69 ($60,000 / 26). Here’s how you’ll calculate FICA tax off of her biweekly gross wages.

For Social Security, multiply her gross wages by .062.

$2,307.69 x .062 = $143.07

For Medicare, multiply her gross wages by .0145.

$2,307.69 x .0145 = $33.46

Adding these two sums together will give us Maria’s total FICA tax.

$143.07 + $33.46 = $176.53

You’ll withhold $176.53 from Maria’s paycheck and make a matching contribution of $176.53 for a total of $353.06.

After you know the amount of taxes to withhold, keep hold of it until you are ready to make your deposit. Likewise, set aside your employer payroll tax obligation, too.

However you choose to store your employee taxes, make sure that it is safe and easy for you to understand and use. You may want to use a separate business or payroll bank account. If you use full-service payroll, the provider will handle this for you.

You must report the withheld tax to the IRS using Form 941 or 944.You can file on paper or through e-file.

Of the two, Form 941 is the most common. The IRS will let you know if you need to use Form 944.

Deposit schedules are either quarterly or annually. Your deposit schedule is determined by the total tax liability reported on Form 941, line 12, or Form 944, line 9, during your lookback period.

Your lookback period helps you figure out the deposit schedule for payroll taxes. A lookback period operates by adding up your quarterly or annual tax liability, the sum of which decides your deposit schedule. For instance, if your total tax liability is under $50,000, you’ll deposit every month. Conversely, if your total tax liability is over $50,000, you’ll deposit semi-weekly.

Here’s how it works.

If you use Form 941, report your taxes quarterly. This system of dividing the year into fiscal quarters will be the same way your lookback period operates. Your lookback period starts July 1 and ends June 30 the next year. So, if you wanted to determine your deposit schedule for 2023, your lookback period would begin July 1, 2021 and end June 30, 2022. Here are the quarters your lookback period would cover for a 2023 deposit schedule:

| Q3 (2021) | Q4 (2021) | Q1 (2022) | Q2 (2022) |

| July 1-Sept 30 | Oct 1-Dec 31 | Jan 1-Mar 31 | Apr 1-June 30 |

By adding up the tax liability of each quarter, you can find your total tax liability for the year.

If you use Form 944, things are more straightforward. Because Form 944 reports your taxes on an annual basis, you don’t have to add up the quarters to understand your total tax liability. Instead, you’ll look at your annual tax liability. But, it can still be a bit tricky.

If you’re using Form 944 to file in the current year or have used it in the past two years, you’ll need to look at your annual tax liability from two years before your current filing period. Filing for 2022? Look at your annual tax liability for 2020.

Once you add up your tax liability using either the quarter or annual method, you’ll be able to find when you need to make your deposits. If your annual tax liability is:

Use the Electronic Federal Tax Payment System for all federal tax deposits.

Even after everything is properly withheld, reported, and deposited, you still have a bit of work to do. Keep detailed records as you go about your work. The information needed to process payroll correctly may also be requested by federal or state agencies. It’s best to be prepared.

Also, make copies of all employee tax information (e.g., employee W-2s, W-4s, and state and local forms.

This is not intended as legal advice; for more information, please click here.